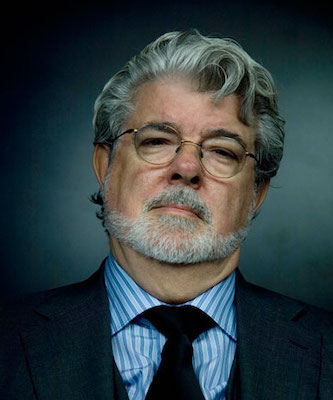

GEORGE LUCAS

The mastermind who redefined the concept of Hollywood motion picture, shifting the focus of film to special effects, production design, and rapid-fire action, and forever altering the ways in which movies are perceived by audiences and studios alike.

ABOUT

Date of Birth

May 14, 1944

FILMS

Companies

Education

From

EARLY LIFE

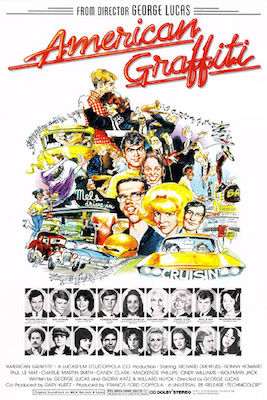

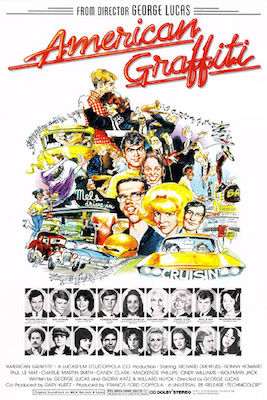

Lucas's parents sold retail office supplies and owned a walnut ranch in California. His experiences growing up in the sleepy suburb of Modesto and his early passion for cars and motor racing would eventually serve as inspiration for his Oscar-nominated low-budget phenomenon, American Graffiti (1973). The son of a small-town stationer and a mother who was often hospitalized for long periods for ill health, Lucas was an early reader of classic adventure stories such as Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe and Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island, an avid collector of comic books, and a keen student of history. He became interested in filmmaking while in high school. He was also a car-racing fanatic as a teenager until a near-fatal crash at age 18 convinced him to give up the sport. Instead, he attended community college and developed a passion for cinematography and camera tricks.

Following the advice of a friend, he transferred to the University of Southern California's film school. While there, future director John Milius, a classmate, introduced Lucas to the work of Japanese director Kurosawa Akira, who would be an important influence on Lucas’s work. Lucas made several highly acclaimed student films, including the futuristic parable Electronic Labyrinth THX 1138 4EB, which took first prize at the National Student Film Festival in 1965. He garnered a comfortable spot under the wing of Francis Ford Coppola, who took an active interest in unleashing new filmmaking talent.

He served a six-month internship in 1967 at Warner Brothers, where he assisted Francis Ford Coppola on Finian’s Rainbow (1968). He followed that experience by shooting a “making-of” documentary about Coppola’s The Rain People (1969). Lucas also shot a portion of the documentary Gimme Shelter (1970), about the violent Rolling Stones concert at the 1969 Altamont Festival, for Albert and David Maysles and Charlotte Zwerin. After working on Gimme Shelter, Lucas (with Coppola's financial assistance) mounted a feature-length remake of THX 1138. The end result, starring Robert Duvall, won rave reviews, and swiftly established itself as a major cult favorite.

The success of THX 1138 brought Lucas to the attention of Universal Studios, which agreed to finance 1973's nostalgic American Graffiti, a superb reminiscence on early-'60s America which launched the motion-picture careers of talents including Richard Dreyfuss, Ron Howard, and Harrison Ford. Even more important was the film's soundtrack, a collection of vintage rock & roll hits which became an immediate best-seller and established the formula for movie soundtracks for decades to come.

Following the advice of a friend, he transferred to the University of Southern California's film school. While there, future director John Milius, a classmate, introduced Lucas to the work of Japanese director Kurosawa Akira, who would be an important influence on Lucas’s work. Lucas made several highly acclaimed student films, including the futuristic parable Electronic Labyrinth THX 1138 4EB, which took first prize at the National Student Film Festival in 1965. He garnered a comfortable spot under the wing of Francis Ford Coppola, who took an active interest in unleashing new filmmaking talent.

He served a six-month internship in 1967 at Warner Brothers, where he assisted Francis Ford Coppola on Finian’s Rainbow (1968). He followed that experience by shooting a “making-of” documentary about Coppola’s The Rain People (1969). Lucas also shot a portion of the documentary Gimme Shelter (1970), about the violent Rolling Stones concert at the 1969 Altamont Festival, for Albert and David Maysles and Charlotte Zwerin. After working on Gimme Shelter, Lucas (with Coppola's financial assistance) mounted a feature-length remake of THX 1138. The end result, starring Robert Duvall, won rave reviews, and swiftly established itself as a major cult favorite.

The success of THX 1138 brought Lucas to the attention of Universal Studios, which agreed to finance 1973's nostalgic American Graffiti, a superb reminiscence on early-'60s America which launched the motion-picture careers of talents including Richard Dreyfuss, Ron Howard, and Harrison Ford. Even more important was the film's soundtrack, a collection of vintage rock & roll hits which became an immediate best-seller and established the formula for movie soundtracks for decades to come.

MOVIES, FAME, FORTUNE

In 1971 Lucas formed the production company Lucasfilm Ltd., which eventually contained a number of divisions, including Industrial Light & Magic (ILM, established 1975), which was regarded as the most prestigious special-effects workshop in American film and assisted other filmmakers and technicians to create the most accomplished visuals possible. Studios scrambled to develop their own sci-fi projects, while Lucas himself turned to studying the pioneering special effects work of innovators like Willis O'Brien and Linwood Dunn, ultimately resulting in ILM. He built his fortune through his movies and their merchandise.

Lucas went back to work on his second film, American Graffiti (1973), a sympathetic recollection of adolescent American life in the early 1960s. It was a surprise success at the box office and was redolent of his youth as a Modesto hot-rodding enthusiast. Shot in less than a month for $780,000, American Graffiti became one of the top grossing films of the decade ($145 million)—and with its modest cast of newcomers (including Richard Dreyfuss, erstwhile child star Ron Howard, and Harrison Fordin) may have been among the most profitable as well. The success of American Graffiti enabled Lucas to finance a project that had been dear to his heart for some time. It earned five Academy Award nominations, including Best Picture, Best Original Screenplay and Best Director for Lucas, and is still considered one of the most successful low budget features ever made.

Lucas went back to work on his second film, American Graffiti (1973), a sympathetic recollection of adolescent American life in the early 1960s. It was a surprise success at the box office and was redolent of his youth as a Modesto hot-rodding enthusiast. Shot in less than a month for $780,000, American Graffiti became one of the top grossing films of the decade ($145 million)—and with its modest cast of newcomers (including Richard Dreyfuss, erstwhile child star Ron Howard, and Harrison Fordin) may have been among the most profitable as well. The success of American Graffiti enabled Lucas to finance a project that had been dear to his heart for some time. It earned five Academy Award nominations, including Best Picture, Best Original Screenplay and Best Director for Lucas, and is still considered one of the most successful low budget features ever made.

Lucasfilm established itself as a “rebel base” of sorts in San Francisco’s Bay Area, a place the filmmaker chose to “shake up the status quo of how movies were made and what they were about.” It was a defiant departure from the Hollywood mainstream and a more conducive atmosphere to cultivate his independent spirit of filmmaking. Science fiction had traditionally been a poor box-office performer, however with Star Wars (1977), which he also wrote, Lucas eschewed the high-tech dystopian allegory then current in science-fiction films in favour of space opera synthesized with vintage Hollywood swashbucklers and frontier adventures.

This space opera set “a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away,” the film centres on Luke Skywalker (played by Mark Hamill), a young man who finds himself embroiled in an interplanetary war between an authoritarian empire and rebel forces. Skywalker, his mentor the wise Jedi Knight Obi-Wan Kenobi (Sir Alec Guinness), and the opportunistic smuggler Han Solo (Ford) are tasked with saving Princess Leia (Carrie Fisher) from captivity on the Death Star, a massive space station commanded by the menacing Darth Vader, whose deep, mechanically augmented voice (contributed by James Earl Jones) became instantly iconic. At the core of the film and the series it initiated are the Jedi Knights—a group of either benevolent or malevolent warriors who harness and manipulate the Force, an all-pervasive spiritual essence that holds in balance the forces of good and evil—and Skywalker’s quest to join their ranks.

Released in May 1977, Star Wars blew audiences away with its awe-inspiring special effects, fantastical landscapes, captivating characters (the erroneous pairing of two bumbling droids providing, ironically, the most heart and comic relief) and the familiar resonance of popular myth and fairy tale. Made for $11 million, the film grossed over $513 million worldwide during its original release creating a cottage industry of toys, comic books, and other collectibles and establishing science fiction as Hollywood's dominant genre. Star Wars was one of the most important and successful films in Hollywood history. The space opera inspired by the writings of Joseph Campbell (as well as, in no small part, Akira Kurosawa's The Hidden Fortress), it incorporated elements of mythology and religion to create a self-contained universe populated by larger-than-life characters in extraordinary situations, all achieved with the latest in cutting-edge technology. The overwhelming success of Star Wars did more than simply alter the kinds of films the studios looked to produce, however; it also forever changed the way films were made. The most notable aspect of the picture's storytelling was its breakneck pacing, edited by Lucas himself in tandem with his wife. Seemingly no film had ever moved so quickly, and its overwhelming success proved not only that a generation weaned on the rapid pace of television could easily absorb such an onslaught of image and sound, but that this was the kind of narrative they wanted to see on a regular basis. The film’s success spawned a host of other science-fiction films using the same special-effects technologies developed at ILM that Star Wars had used so effectively.

Lucas served as executive producer of the other two episodes in the Star Wars saga, The Empire Strikes Back (1980) and Return of the Jedi (1983). In the meantime, he set up a state-of-the-art special effects company, Industrial Light & Magic (ILM), as well as a sound studio, Skywalker Sound, and began to execute more control over the finished product of his films. He eventually built his own moviemaking "empire" outside of the controlling influence of Hollywood in the hills of Marin Country, California.

Working exclusively as a producer throughout the 1980s and most of the ’90s, Lucas had a few minor successes (Willow, 1988) and spectacular failures (Howard the Duck, 1986). He fulfilled a long-standing ambition by serving as executive producer on Kurosawa’s Kagemusha (1980).

Released in May 1977, Star Wars blew audiences away with its awe-inspiring special effects, fantastical landscapes, captivating characters (the erroneous pairing of two bumbling droids providing, ironically, the most heart and comic relief) and the familiar resonance of popular myth and fairy tale. Made for $11 million, the film grossed over $513 million worldwide during its original release creating a cottage industry of toys, comic books, and other collectibles and establishing science fiction as Hollywood's dominant genre. Star Wars was one of the most important and successful films in Hollywood history. The space opera inspired by the writings of Joseph Campbell (as well as, in no small part, Akira Kurosawa's The Hidden Fortress), it incorporated elements of mythology and religion to create a self-contained universe populated by larger-than-life characters in extraordinary situations, all achieved with the latest in cutting-edge technology. The overwhelming success of Star Wars did more than simply alter the kinds of films the studios looked to produce, however; it also forever changed the way films were made. The most notable aspect of the picture's storytelling was its breakneck pacing, edited by Lucas himself in tandem with his wife. Seemingly no film had ever moved so quickly, and its overwhelming success proved not only that a generation weaned on the rapid pace of television could easily absorb such an onslaught of image and sound, but that this was the kind of narrative they wanted to see on a regular basis. The film’s success spawned a host of other science-fiction films using the same special-effects technologies developed at ILM that Star Wars had used so effectively.

Lucas served as executive producer of the other two episodes in the Star Wars saga, The Empire Strikes Back (1980) and Return of the Jedi (1983). In the meantime, he set up a state-of-the-art special effects company, Industrial Light & Magic (ILM), as well as a sound studio, Skywalker Sound, and began to execute more control over the finished product of his films. He eventually built his own moviemaking "empire" outside of the controlling influence of Hollywood in the hills of Marin Country, California.

Working exclusively as a producer throughout the 1980s and most of the ’90s, Lucas had a few minor successes (Willow, 1988) and spectacular failures (Howard the Duck, 1986). He fulfilled a long-standing ambition by serving as executive producer on Kurosawa’s Kagemusha (1980).

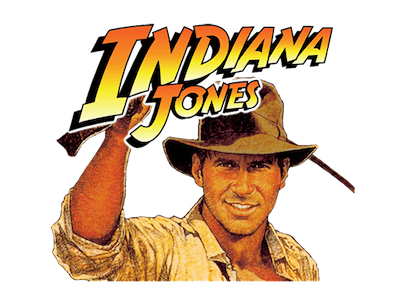

Overlapping with his work on Star Wars, Lucas developed a new adventure series featuring a tough but humorous archaeologist named Indiana Jones. He cast Star Wars antihero Ford in the title role, and Steven Spielberg signed on as director for Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), the first film in the franchise with Lucas as the executive producer. Instead of deep space, Indiana Jones battles the Nazis over the Ark of the Covenant. Lucas helped create the stories and worked as a producer on the two sequels that followed. Ford starred with Kate Capshaw (Spielberg's future wife) in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984), and in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989), audiences got to meet the hero's father, played by Sean Connery.

In 1997 he added new computerized effects to the Star Wars films and reissued them to great box-office success, though critics were less enthusiastic. Those films generated interest for one of the most highly anticipated releases of the decade, Star Wars: Episode I—The Phantom Menace (1999), the first installment in a prequel trilogy about the young Jedi knight Anakin Skywalker. For that film, which received mixed reviews but reaped enormous profits, Lucas returned to the director’s chair for the first time in more than 20 years, as he had foreseen doing in 1977. Defending his latest creation, Lucas argued that The Phantom Menace was a children's movie, as all the Star Wars movies were meant to be before their cult-like magnetism took hold of the American public.

In 1997 he added new computerized effects to the Star Wars films and reissued them to great box-office success, though critics were less enthusiastic. Those films generated interest for one of the most highly anticipated releases of the decade, Star Wars: Episode I—The Phantom Menace (1999), the first installment in a prequel trilogy about the young Jedi knight Anakin Skywalker. For that film, which received mixed reviews but reaped enormous profits, Lucas returned to the director’s chair for the first time in more than 20 years, as he had foreseen doing in 1977. Defending his latest creation, Lucas argued that The Phantom Menace was a children's movie, as all the Star Wars movies were meant to be before their cult-like magnetism took hold of the American public.

Lucas followed with Star Wars: Episode II—Attack of the Clones (2002) and Star Wars: Episode III—Revenge of the Sith (2005), both of which he also directed, before returning to an executive production role on the fourth Indiana Jones film, Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008), which Spielberg directed. Ford returned as the famed adventuring archaeologist in Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull, and was joined by Cate Blanchett and Shia LaBeouf on this new challenge. The film proved one of the summer's biggest hits.

Lucas created two animated television series, Star Wars: Clone Wars (2003–05) and Star Wars: The Clone Wars (2008–13). He was then executive producer of Red Tails (2012), an action-packed account of the Tuskegee Airmen and his first film in nearly two decades that was not affiliated with either the Star Wars or Indiana Jones franchises. He was able to help bring the story of the famed African-American pilots known as the Tuskegee Airmen to the big screen. This World War II drama starred Cuba Gooding Jr., Terrence Howard, Nate Parker and David Oyelowo. Red Tails may prove to be one of Lucas's final epics, excluding a possible new Indiana Jones film. He announced that he was retiring from big blockbusters to explore smaller, more personal stories on the screen around this time.

Lucas created two animated television series, Star Wars: Clone Wars (2003–05) and Star Wars: The Clone Wars (2008–13). He was then executive producer of Red Tails (2012), an action-packed account of the Tuskegee Airmen and his first film in nearly two decades that was not affiliated with either the Star Wars or Indiana Jones franchises. He was able to help bring the story of the famed African-American pilots known as the Tuskegee Airmen to the big screen. This World War II drama starred Cuba Gooding Jr., Terrence Howard, Nate Parker and David Oyelowo. Red Tails may prove to be one of Lucas's final epics, excluding a possible new Indiana Jones film. He announced that he was retiring from big blockbusters to explore smaller, more personal stories on the screen around this time.

Apart from the films he directed and produced, among them some of the most-profitable productions in Hollywood history, Lucas enjoyed as part of his legacy Lucasfilm’s network of properties, studios, and subsidiary companies. In October 2012 the Walt Disney Company purchased Lucasfilm for $4 billion and Disney got the rights to the very lucrative Star Wars franchise. They announced that it would make a third Star Wars trilogy. The first entry, Star Wars: Episode VII—The Force Awakens, was released in 2015. Subsequent films included Star Wars: Episode VIII—The Last Jedi (2017) as well as A Star Wars Story series, which comprised stand-alone movies.

PERSONAL LIFE

In addition to being a filmmaker, Lucas has been dedicated to helping improve education through the George Lucas Educational Foundation. Created in the early 1990s, the organization encourages the use of project-based and team-based learning, among other education reforms. The foundation's mission is deeply personal to Lucas, who spent many years as a single father to his adopted daughter Amanda after his divorce from film editor Marcia (Griffin) Lucas in 1983. Following their split, Lucas also adopted two more children, Katie and Jett.

In January 2013, Lucas announced his engagement to Mellody Hobson, president of Ariel Investments. The couple had been dating for five years prior to their engagement. The 69-year-old Lucas and 44-year-old Hobson wed in late June 2013 at Skywalker Ranch in Marin County, California. Shortly afterward, they welcomed daughter Everest to the family. Lucas was able to construct Skywalker Ranch in San Francisco’s North Bay in the early ‘80s, a place where filmmakers could work together sharing ideas and experience.

In January 2013, Lucas announced his engagement to Mellody Hobson, president of Ariel Investments. The couple had been dating for five years prior to their engagement. The 69-year-old Lucas and 44-year-old Hobson wed in late June 2013 at Skywalker Ranch in Marin County, California. Shortly afterward, they welcomed daughter Everest to the family. Lucas was able to construct Skywalker Ranch in San Francisco’s North Bay in the early ‘80s, a place where filmmakers could work together sharing ideas and experience.

Lucas has a reputation for being quiet on the media front, so not much is known about how he spends his fortune. However, he has cultivated a California real-estate portfolio, including Skywalker Ranch, and donates a lot of his money to charity. He is now focused on philanthropy: his charitable family foundation has more than $1 billion in assets.

The Lucas Museum of Narrative Art will open in Los Angeles in 2020 and is entirely funded by Lucas and his wife, Mellody Hobson. The Lucas Museum of Narrative Art will inspire current and future generations through the universal art of visual storytelling. The museum will present permanent collections and rotating exhibitions for diverse public audiences which will feature illustrations, paintings, comic art, photography, and an in-depth exploration of the arts of filmmaking (including storyboards, costumes, animation, visual effects, and more). Extensive education programming designed for all ages will explore innovative ways for visitors to engage with narrative art.

The Lucas Museum of Narrative Art will open in Los Angeles in 2020 and is entirely funded by Lucas and his wife, Mellody Hobson. The Lucas Museum of Narrative Art will inspire current and future generations through the universal art of visual storytelling. The museum will present permanent collections and rotating exhibitions for diverse public audiences which will feature illustrations, paintings, comic art, photography, and an in-depth exploration of the arts of filmmaking (including storyboards, costumes, animation, visual effects, and more). Extensive education programming designed for all ages will explore innovative ways for visitors to engage with narrative art.

Lucas was named a Kennedy Center honoree in 2015.

Created by the National Cultural Center Act of 1958, the facility was renamed as a “living memorial” to the assassinated president John F. Kennedy, the first American president to take an active interest in promoting the performing arts. It hosts a variety of theatre, dance, and musical performances, both national and international, and is the home of the National Symphony Orchestra as well as the DeVos Institute of Arts Management. Since 1978 it has been the site of an annual gala at which a number of performers are awarded the Kennedy Center Honors.

"The best way to pursue happiness is to help other people. Nothing else will make you happier."

"Always remember, your focus determines your reality."

"It's okay to lose; just don't lose the lesson."

"You have to find something that you love enough to be able to take risks, jump over hurdles and break through brick walls that are always going to be placed in front of you."

SOURCES

“American Graffiti (7/10) Movie CLIP - Must Be Your Mama's Car (1973) HD.” YouTube, uploaded by Movieclips, June 28, 2011, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z2OoxzYqgNY.

Barson, Michael. “George Lucas.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 26 Dec. 2019, www.britannica.com/biography/George-Lucas.

Brocavich, Alan. “A Reel Opinion: The Legacy of George Lucas.” Reel Speak, reelspeak.blogspot.com/2015/11/a-reel-opinion-legacy-of-george-lucas.html.

Cascone, Sarah. “What Is a 'Narrative Art Museum'? 6 Things to Expect From George Lucas's New LA Museum.” Artnet News, 21 May 2018, news.artnet.com/art-world/what-is-a-narrative-art-museum-george-lucas-1258994.

Chinchot, Franz. “¡Por Primera Vez Lucasfilm Tendrá Pabellón En D23! ⋆ Disney Fans.” Disney Fans, 11 July 2019, disneyfans.mx/2019/07/11/por-primera-vez-lucasfilm-tendra-pabellon-en-d23/.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 5 Dec. 2018, www.britannica.com/topic/Kennedy-Center-for-the-Performing-Arts.

Editors, Biography.com. “George Lucas.” Biography.com, A&E Networks Television, 15 Aug. 2019, www.biography.com/filmmaker/george-lucas. Editors, Lucasfim. “Lucasfilm Company History: Lucasfilm Ltd.” Lucasfilm, www.lucasfilm.com/who-we-are/our-story/.

Forbes. “George Lucas.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, www.forbes.com/profile/george-lucas/#71b5ed436e63. Frei, Vincent. “INDUSTRIAL LIGHT & MAGIC: London and Vancouver Expansion Plans.” The Art of VFX, 18 Apr. 2014, www.artofvfx.com/industrial-light-magic-london-and-vancouver-expansion-plans/. “George Lucas: Staty.” Pinterest, www.pinterest.dk/pin/497014508856450955/.

“HD - Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) Theatrical Trailer.” YouTube, uploaded by HDMovieTrailerscom, Sept. 24, 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XkkzKHCx154.

Hoffower, Hillary. “George Lucas Is One of America's Wealthiest Celebrities. Here's a Look at How the 'Star Wars' Creator Built and Spends His $6.4 Billion Fortune.” Business Insider, Business Insider, 20 Dec. 2019, www.businessinsider.com/star-wars-george-lucas-net-worth-movies-house-spending-2019-7#convinced-the-original-star-wars-would-be-a-flop-fox-the-films-distributor-let-lucas-give-up-an-additional-500000-in-directing-fees-in-exchange-for-ownership-of-licensing-and-merchandising-rights-11.

“Indiana Jones.” Disney Wiki, disney.fandom.com/wiki/Indiana_Jones.

Lazarov, AuthorGeorgi Lazarov Georgi, et al. “Top 20 Most Inspirational George Lucas Quotes.” MotivationGrid, 20 Mar. 2018, motivationgrid.com/top-20-inspirational-george-lucas-quotes/. Lucas, George. “The Lucas Museum of Narrative Art.” About the Museum - The, 2020, lucasmuseum.org/museum.

Lynda Miles, Michael Pye. “The Man Who Made Star Wars.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 14 May 2018, www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1979/03/the-man-who-made-star-wars/306228/.

McMahon, James. “Seth Rogen: 'George Lucas Believes the World Will End in 2012': NME.” NME Music News, Reviews, Videos, Galleries, Tickets and Blogs | NME.COM, 18 Jan. 2011, www.nme.com/news/seth-rogen-george-lucas-believes-the-world-will-en-878054.

“Millennium Falcon Dorsal View: Star Wars Art, Star Wars Wallpaper, Star Wars Spaceships.” Pinterest, Patrick Reilly, www.pinterest.com/pin/366761963399157854/.

“Monico Movies- American Graffiti (12A).” Rhiwbina Info, 5 Jan. 2020, www.rhiwbina.info/event/monico-movies-american-graffiti-12a/.

“Red Tails (2012) HD Movie Trailer - Lucasfilm Official Trailer.” YouTube, uploaded by Movieclips Trailers, June 29, 2011, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BpA6TC0T_Lw.

RottenTomatoes. “George Lucas.” Rotten Tomatoes, www.rottentomatoes.com/celebrity/george_lucas.

“Skywalker Ranch.” Anna Khalatyan, 7 Feb. 2018, anna.khalatyan.com/?p=32.

“Skywalker Ranch.” Skywalker Sound, www.skysound.com/ranch/.

“Skywalker Sound.” Disney Wiki, FANDOM, disney.fandom.com/wiki/Skywalker_Sound. “Star Wars (1977) original opening crawl.” YouTube, uploaded by allluckyseven, April 19, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iXDnFYu91vY.

“Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace - Trailer.” YouTube, uploaded by Star Wars, July 5, 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bD7bpG-zDJQ. Toscano, Tony. “Happy Birthday 'Howard the Duck'; Film Turns 30 Today.” Gephardt Daily, 1 Aug. 2016, gephardtdaily.com/entertainment/happy-birthday-howard-the-duck-film-turns-30-today/.

University of Southern California. “Usc-Square-White.” USC Rossier School of Education, rossier.usc.edu/usc-officials-convene-to-strategize-on-stem-on-1114/usc-square-white/. https://pngimage.net/r2d2-c3po-png/

Barson, Michael. “George Lucas.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 26 Dec. 2019, www.britannica.com/biography/George-Lucas.

Brocavich, Alan. “A Reel Opinion: The Legacy of George Lucas.” Reel Speak, reelspeak.blogspot.com/2015/11/a-reel-opinion-legacy-of-george-lucas.html.

Cascone, Sarah. “What Is a 'Narrative Art Museum'? 6 Things to Expect From George Lucas's New LA Museum.” Artnet News, 21 May 2018, news.artnet.com/art-world/what-is-a-narrative-art-museum-george-lucas-1258994.

Chinchot, Franz. “¡Por Primera Vez Lucasfilm Tendrá Pabellón En D23! ⋆ Disney Fans.” Disney Fans, 11 July 2019, disneyfans.mx/2019/07/11/por-primera-vez-lucasfilm-tendra-pabellon-en-d23/.

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. “Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., 5 Dec. 2018, www.britannica.com/topic/Kennedy-Center-for-the-Performing-Arts.

Editors, Biography.com. “George Lucas.” Biography.com, A&E Networks Television, 15 Aug. 2019, www.biography.com/filmmaker/george-lucas. Editors, Lucasfim. “Lucasfilm Company History: Lucasfilm Ltd.” Lucasfilm, www.lucasfilm.com/who-we-are/our-story/.

Forbes. “George Lucas.” Forbes, Forbes Magazine, www.forbes.com/profile/george-lucas/#71b5ed436e63. Frei, Vincent. “INDUSTRIAL LIGHT & MAGIC: London and Vancouver Expansion Plans.” The Art of VFX, 18 Apr. 2014, www.artofvfx.com/industrial-light-magic-london-and-vancouver-expansion-plans/. “George Lucas: Staty.” Pinterest, www.pinterest.dk/pin/497014508856450955/.

“HD - Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) Theatrical Trailer.” YouTube, uploaded by HDMovieTrailerscom, Sept. 24, 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XkkzKHCx154.

Hoffower, Hillary. “George Lucas Is One of America's Wealthiest Celebrities. Here's a Look at How the 'Star Wars' Creator Built and Spends His $6.4 Billion Fortune.” Business Insider, Business Insider, 20 Dec. 2019, www.businessinsider.com/star-wars-george-lucas-net-worth-movies-house-spending-2019-7#convinced-the-original-star-wars-would-be-a-flop-fox-the-films-distributor-let-lucas-give-up-an-additional-500000-in-directing-fees-in-exchange-for-ownership-of-licensing-and-merchandising-rights-11.

“Indiana Jones.” Disney Wiki, disney.fandom.com/wiki/Indiana_Jones.

Lazarov, AuthorGeorgi Lazarov Georgi, et al. “Top 20 Most Inspirational George Lucas Quotes.” MotivationGrid, 20 Mar. 2018, motivationgrid.com/top-20-inspirational-george-lucas-quotes/. Lucas, George. “The Lucas Museum of Narrative Art.” About the Museum - The, 2020, lucasmuseum.org/museum.

Lynda Miles, Michael Pye. “The Man Who Made Star Wars.” The Atlantic, Atlantic Media Company, 14 May 2018, www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1979/03/the-man-who-made-star-wars/306228/.

McMahon, James. “Seth Rogen: 'George Lucas Believes the World Will End in 2012': NME.” NME Music News, Reviews, Videos, Galleries, Tickets and Blogs | NME.COM, 18 Jan. 2011, www.nme.com/news/seth-rogen-george-lucas-believes-the-world-will-en-878054.

“Millennium Falcon Dorsal View: Star Wars Art, Star Wars Wallpaper, Star Wars Spaceships.” Pinterest, Patrick Reilly, www.pinterest.com/pin/366761963399157854/.

“Monico Movies- American Graffiti (12A).” Rhiwbina Info, 5 Jan. 2020, www.rhiwbina.info/event/monico-movies-american-graffiti-12a/.

“Red Tails (2012) HD Movie Trailer - Lucasfilm Official Trailer.” YouTube, uploaded by Movieclips Trailers, June 29, 2011, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BpA6TC0T_Lw.

RottenTomatoes. “George Lucas.” Rotten Tomatoes, www.rottentomatoes.com/celebrity/george_lucas.

“Skywalker Ranch.” Anna Khalatyan, 7 Feb. 2018, anna.khalatyan.com/?p=32.

“Skywalker Ranch.” Skywalker Sound, www.skysound.com/ranch/.

“Skywalker Sound.” Disney Wiki, FANDOM, disney.fandom.com/wiki/Skywalker_Sound. “Star Wars (1977) original opening crawl.” YouTube, uploaded by allluckyseven, April 19, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iXDnFYu91vY.

“Star Wars Episode I: The Phantom Menace - Trailer.” YouTube, uploaded by Star Wars, July 5, 2012, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bD7bpG-zDJQ. Toscano, Tony. “Happy Birthday 'Howard the Duck'; Film Turns 30 Today.” Gephardt Daily, 1 Aug. 2016, gephardtdaily.com/entertainment/happy-birthday-howard-the-duck-film-turns-30-today/.

University of Southern California. “Usc-Square-White.” USC Rossier School of Education, rossier.usc.edu/usc-officials-convene-to-strategize-on-stem-on-1114/usc-square-white/. https://pngimage.net/r2d2-c3po-png/